Ponzi schemes are a classic form of investment fraud. Early investors are solicited with the promise of high returns and low risk. They are given falsely encouraging reports about the performance of their investments and may receive early distributions of purported “profits” misappropriated from the accounts of other investors. Although the first round of investors may make money on the deal, subsequent participants are at serious risk of a total loss.

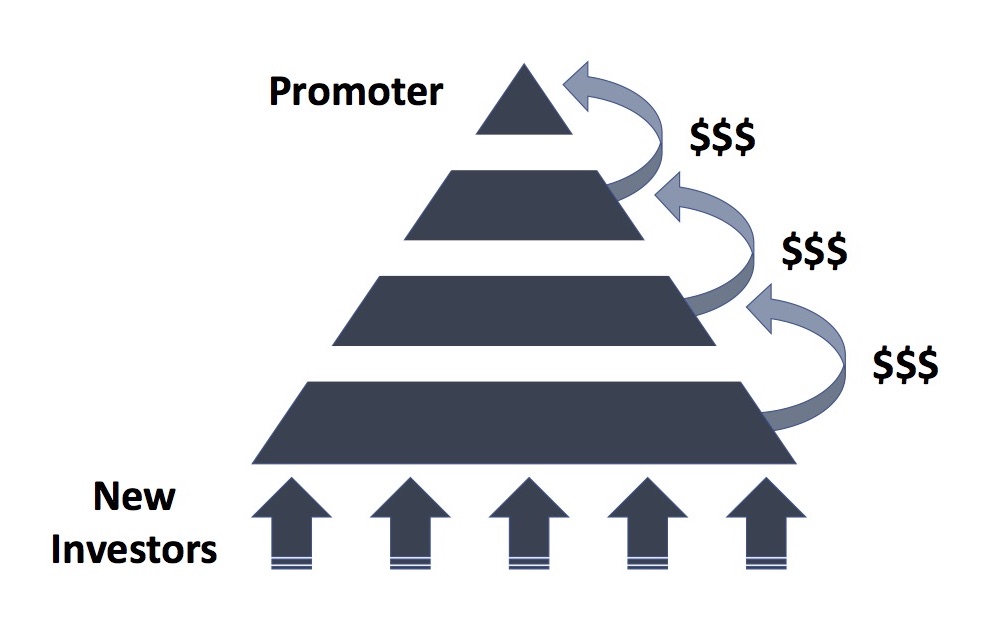

These frauds are often compared to pyramid schemes, in which proceeds from the newest participants – who form the bottom base of the pyramid – are used to pay earlier investors in the upper levels. The promoter presides from the top, orchestrating the flow of funds and pocketing as much cash as possible.

The promoter of a Ponzi scheme faces continuous pressure to solicit and attract new victims. Initial investors may be asked to recruit friends and family and others through positive testimonials and word of mouth.

Many promoters of Ponzi schemes force investors to agree to a lengthy lock-up period, because requests for withdrawals or redemptions can trigger a liquidity crunch. As soon as the steady flow of new funds is shut off, these frauds collapse because the promoter can no longer afford to pay fake ‘profits’ to investors. Yet despite the constant risk of exposure, many such schemes are not discovered to be fraudulent until the promoter disappears with the money.

Charles Ponzi – for whom the scheme is named – pioneered the technique during the decade before the Great Depression. He made around $20 million (equivalent to $250 million in today's economy) by persuading victims he could deliver 50% to 90% returns through the trade and arbitrage of international postage stamps.

The size and ambition of such schemes has grown considerably since that time. The most notorious contemporary example is Bernie Madoff, whose fraud scheme ran smoothly for decades until collapsing in 2008. The following year, Madoff was sentenced to 150 years in prison and ordered to pay restitution of $170 billion.

Promising 'The Next Big Thing'

Promoters of Ponzi schemes are often savvy trend-spotters who borrow facts from newsworthy technologies and new innovations when developing their sales pitch. They aim to attract investors who are eager to reap profits from 'the next big thing' such as cryptocurrency or artificial intelligence. Below is one example.

In January 2018, the Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC) announced a court enforcement action against promoters of a purported digital currency known as "My Big Coin" who solicited $6 million from investors. Those investors were presumably seeking to recreate the same market magic associated with Bitcoin, which had recently skyrocketed in value. Yet despite promises by the promoters, My Big Coin was never, in fact, actively traded on any currency exchanges, nor was it 'backed by gold' as they claimed, according to the CFTC. Nearly all funds solicited from investors were allegedly misappropriated. The promoters transferred customer funds into their personal bank accounts, and used the money to pay for fine art, travel and luxury goods, according to the complaint.

There have been many perpetrators of Ponzi schemes whose names have not made headlines – and whose frauds are still active and attracting new victims.

About the Author

Consult an Investigator

If you suspect you are a victim of a Ponzi scheme, and would like to discuss a potential investigation, please complete the form below. You can also speak with an investigator by contacting our offices at 800-580-8755.